Cases can take years to move through our judicial system. The labor dispute in Glacier Northwest, Inc. v. International Brotherhood of Teamsters, which has been pending for over four years, is one such case. Over this summer, our interns assisted with research for the amicus brief Landmark submitted in this case at the petition for cert. stage. On January 10, these interns were able to see the culmination of the case when they attended oral arguments for Glacier at the United States Supreme Court.

To ensure a seat during the oral argument, prospective attendees should arrive in line by at least 5:30 in the morning. Not taking any chances, Landmark’s interns arrived in front of the Court at 3:30 a.m. From their place as the very first ones in line, the interns braved freezing temperatures but enjoyed a stunning view of the U.S. Capitol Dome. By the time they were allowed into the Court, shortly after 9 a.m., the line had swelled to over 50 people. Only the first 25 of them were issued the first round of tickets.

To ensure a seat during the oral argument, prospective attendees should arrive in line by at least 5:30 in the morning. Not taking any chances, Landmark’s interns arrived in front of the Court at 3:30 a.m. From their place as the very first ones in line, the interns braved freezing temperatures but enjoyed a stunning view of the U.S. Capitol Dome. By the time they were allowed into the Court, shortly after 9 a.m., the line had swelled to over 50 people. Only the first 25 of them were issued the first round of tickets.

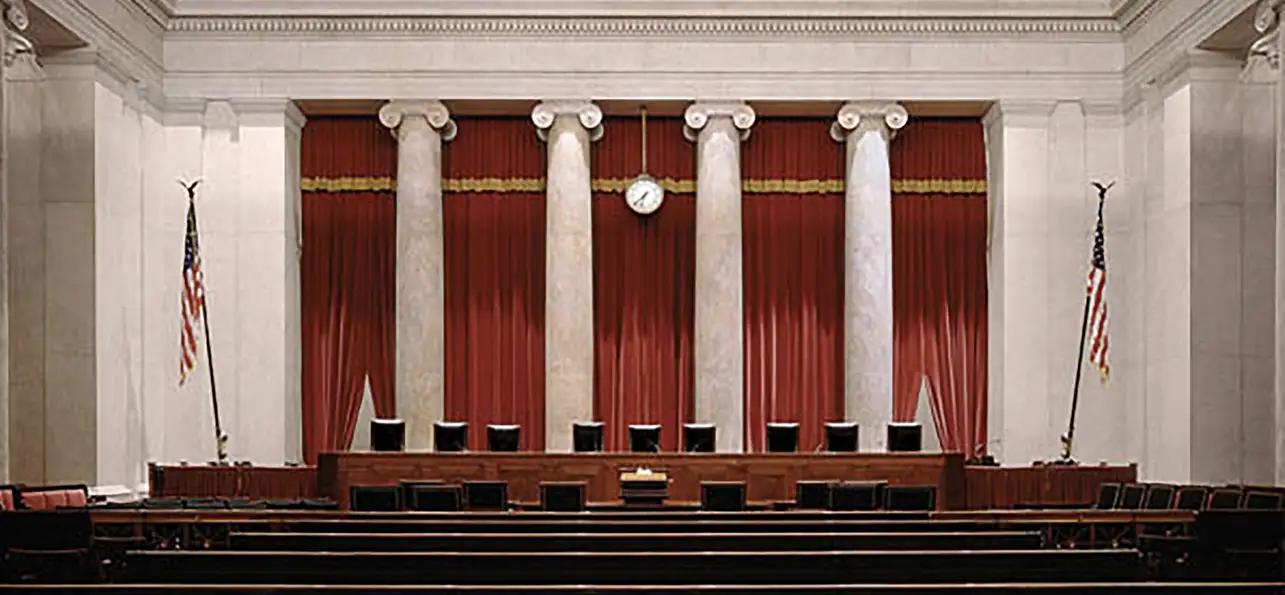

Both inside and out, the Court is an aesthetic monument to the virtues of the Constitution. Its sprawling marble interior is filled with depictions of esteemed Justices past. Among the highlights are a sculpture of Chief Justice John Marshall and an official portrait of the late, great Justice Antonin Scalia. The Courtroom itself is brimming with symbolism. Dramatically warm lighting illuminates the justices as they emerge from behind their crimson veil as the Court opened proceedings. The public, meanwhile, gathers on a level plane with the advocates bringing their case before the nation’s highest court. The entire scene is framed at the top of the room’s curtained walls by enormous friezes highlighting the “great lawgivers in history.” Everything that happens in the Courtroom takes place under the watchful eyes of Moses, Hammurabi, and King John I, among many others. The message is clear: the American legal system culminates millennia of legal development. Solidifying this point, as the Court came into session the Marshal of the Court ordered all to ‘Oyez, oyez, oyez.” This same French phrase has been used for a thousand years of Norman, English, and now American common law proceedings.

framed at the top of the room’s curtained walls by enormous friezes highlighting the “great lawgivers in history.” Everything that happens in the Courtroom takes place under the watchful eyes of Moses, Hammurabi, and King John I, among many others. The message is clear: the American legal system culminates millennia of legal development. Solidifying this point, as the Court came into session the Marshal of the Court ordered all to ‘Oyez, oyez, oyez.” This same French phrase has been used for a thousand years of Norman, English, and now American common law proceedings.

The Supreme Court of the United States stands in direct contrast to its counterparts around the globe, a testament to the pride in which we hold the sanctity of the rule of law. In the majority of countries, their highest courts are undecorated and purely functional, indistinguishable from an upscale corporate conference room. Our judicial branch and the Constitution it interprets has survived for 236 years unbroken. The dramatic halls and customs of our U.S. Supreme Court extol that history.

Despite the awesome scenery, the U.S. Marshals remind all visitors that cameras are not allowed in the courtroom. This adds to the wonder and mystery of the place. The introduction of cameras in the courtroom has been forbidden since 1946. In 1999, Senator Chuck Grassley proposed legislation that would allow cameras into the courtroom, but such measures have failed to gain any traction. During the course of this debate over public photography in the Court, various Justices have issued opinions regarding the camera’s inclusion. The core of this debate centers around distrust in other institutions and wariness about cameras’ effects on Court proceedings. In 2005, Justice Antonin Scalia cited a distrust of the media and their “15-second takeouts on the network news” as “misinform[ing] the public rather than inform[ing] the public.” In 2007, Justice Anthony Kennedy worried about how colleagues might feel the need to say “something for a soundbite,” introducing an “insidious dynamic into what is now a collegial Court.”

The lack of cameras in the Courtroom ensures the Justices are not focused on generating newsworthy soundbites for their partisan fans. As a result of this, the interns were surprised with how the Justices interacted and how they composed themselves. Justices Alito and Thomas reclined in their chair, while Justice Kavanaugh casually joked with his new neighbor, Justice Jackson. Both had inquisitive expressions throughout, but Kavanaugh didn’t ask a single question. The Supreme Court is one of the last truly collegial institutions of governance still operating in the United States, and the lack of cameras has helped to preserve that.

The arguments themselves ranged over a complicated set of jurisdictional questions and doctrinal tests. A decision in Glacier could carry widespread implications across American labor law, leading the Justices to engage in vigorous questioning against both parties. Landmark has addressed a fuller forecast of the arguments’ impacts in this earlier blog post. For our interns, it was an invigorating mental exercise to observe our nation’s top advocates unravel the most complex legal issues of the day. Among those arguing before the Court were former U.S. Solicitor General Noel Francisco, the sitting Assistant U.S. Solicitor General, and an experienced union lawyer.

……………………

The interns were grateful for their experience inside the nerve center of constitutional debate. The next generation of conservative lawyers is shaping up to become an informed and committed class of patriots.

SUPPORT LANDMARK LEGAL FOUNDATION

We are truly facing existential threats to our individual rights and liberties, the Constitution, and our national character. If unchallenged, this assault on our very way of life will ruin our great nation. With your financial and moral support, Landmark is not going to let that happen without a fight. Will you join us?