Trump v. Anderson:

Supreme Court Overturns Colorado Supreme Court

Trump Not Disqualified Under the 14th Amendment

Major Issues Explained

UPDATE 3/5/24:

Today, in Trump v. Anderson the U.S. Supreme Court in a per curiam opinion overruled the Colorado Supreme Court’s finding that Donald Trump is ineligible to run for President under Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. This ruling is a win for democracy and ensures that partisan state officials cannot decide national elections and disenfranchise millions of American voters.

“The president is supposed to be chosen at the ballot box – not in a Colorado courtroom,” stated Michael J. O’Neill, Landmark’s Vice President for Legal Affairs. O’Neill continued, “A slim majority of the Colorado Supreme Court made the unprecedented decision to disenfranchise millions and the U.S. Supreme Court had to step in. This is a win for our representative republic.”

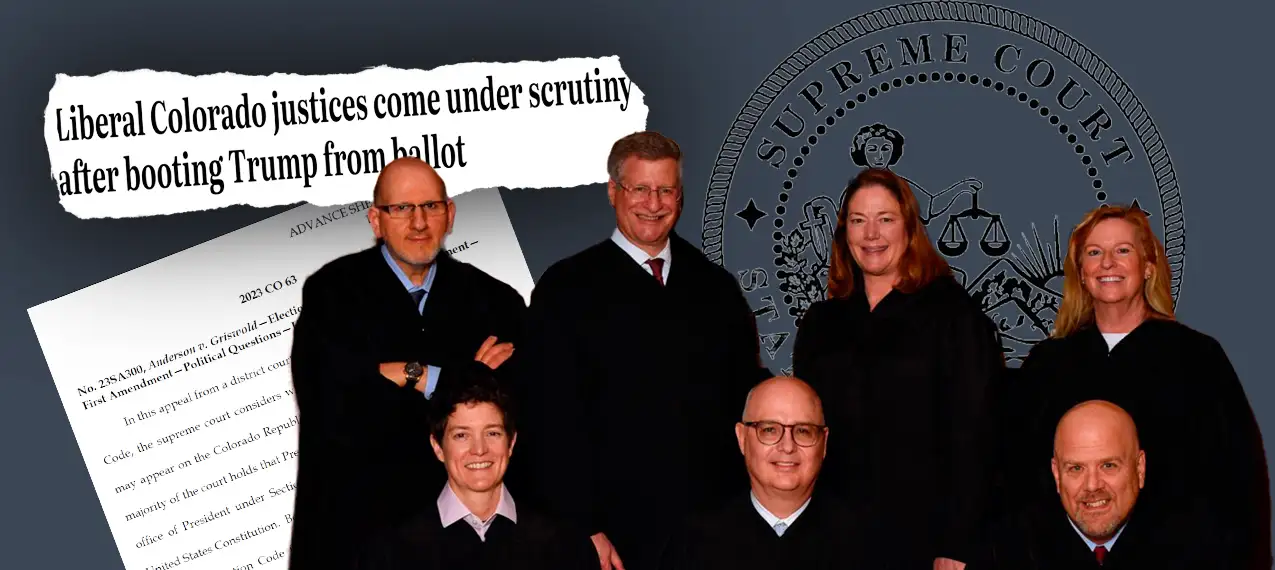

Several months ago, the Colorado Supreme Court – in reversing a lower state court’s ruling – concluded that Section 3 of the 14th Amendment disqualifies Donald Trump from appearing on the Republican primary ballot. In short, the Colorado Supreme Court found that, on January 6, 2021, and in the days leading up to it, Mr. Trump had engaged in insurrection thereby disqualifying him from running and serving as president.

In a per curiam decision, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision. The U.S. Supreme Court concluded that “States have no power under the Constitution to enforce Section 3 of the 14th Amendment with respect to federal offices, especially the Presidency.” Upholding the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision would mean that individual states have more authority than Congress to determine how a provision of the Constitution intended to limit state power should be enforced with respect to federal offices. Such an interpretation, in the words of the Court “is simply implausible.”

Finally, the Court notes the practical effects of upholding Colorado’s decision. A “state-by-state resolution of the question whether Section 3 bars a particular candidate for President from serving would be quite unlikely to yield a uniform answer consistent with the basic principle that ‘the President… represent[s] all the voters in the Nation.’” In other words, “a single candidate would be declared ineligible in some States, but not others, based on the same conduct (and perhaps even the same factual record).”

All nine members of the Court agree that Colorado cannot keep a presidential candidate off the ballot for being disqualified under Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

UPDATE:

Chaos Scenarios Stemming From

Potential Supreme Court Ruling

The Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Trump v. Anderson on February 8, 2024, and focused primarily on two arguments: 1) whether Donald Trump was covered by Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment as an “officer of the United States;” and 2) whether Section Three is “self-executing.” The first issue disposes of the entire case. If Trump was not an “officer of the United States” on January 6, 2021, then all the other questions, such as whether he engaged in insurrection, become irrelevant. The second grounds focused on whether Section Three gives states the power to enforce its disqualification provision, or whether enforcement rests exclusively with Congress. If the Court decides this case in favor of President Trump on the second grounds, then the door will be left open for Congress to intervene in the future and trigger some chaotic scenarios that could spark a full-blown constitutional crisis. An amicus brief filed by Edward Foley, Benjamin Ginsberg, and Richard Hasen discusses these scenarios. Brief of Amici Curiae Edward B. Foley, Benjamin L. Ginsberg, and Richard L. Hasen in Support of Neither Party, Trump v. Anderson, No. 23-719 (2024).

Imagine President Trump wins the Electoral College in the 2024 general election. However, Democrats win control of the House and Senate. On January 6, 2025, after the new Congress has been sworn in, a fifth of each chamber raises a Section Three objection to the certification of the electoral college votes, arguing Donald Trump is ineligible to serve as president and therefore the election was not “regularly given.” 3 U.S.C. § 15 (d)(2)(B)(ii)(II). This would trigger separate votes on the objection in the House and in the Senate per the Electoral Count Reform Act (ECRA). 3 U.S.C. § 15 (d)(2). In this scenario, both chambers of the Democrat-controlled Congress vote in favor of resolutions to disqualify Trump under Section 3. Then what? The answer is unclear, but it is most likely that the election would then be conducted by the House of Representatives. The power to conduct an election is provided to them under the Twelfth Amendment in circumstances when no candidate has reached the requisite 270 electoral college votes needed to win. U.S. Const. Amend. XII. This allows a Democrat-controlled House to select Joe Biden as president, because he is the only candidate to win electoral college votes who is also not disqualified. This would be chaotic enough; Republicans would likely be exceptionally outraged at such a decision. However, there arises the additional problem of whether the House has this power, or whether the Twentieth Amendment would take effect. The relevant part of the Twentieth Amendment states “if the President elect shall have failed to qualify, then the Vice President elect shall act as President.” This language suggests Trump’s Vice President would take over rather than Joe Biden. U.S. Const. Amend. XX § 3. The nation would be in the throes of a dangerous constitutional crisis.

Chaos would also arise under another less likely, but still possible scenario. Here, neither Trump nor Biden wins 270 electoral votes, either by splitting the count 269-269 or by both being denied a majority by a third-party candidate. In this scenario, furthermore, the Democrats win the House of Representatives, and the Republicans take the Senate. Once again, during the January 6 electoral vote certification, the requisite number of members in each chamber objects to counting votes for Donald Trump due to his purported violation of Section Three. The chambers then would hold separate votes on disqualification. This time, the House votes in favor but the Senate votes against. The motion to disqualify being defeated, the electoral vote counting would continue as normal. However, due to no one candidate reaching 270 electoral college votes, the election would be determined by the Democrat-controlled House, per the Twelfth Amendment. The Democrats could, in this House electoral process, choose to disqualify Trump under Section Three, and then vote to make Joe Biden president. This would once again potentially lead to a major crisis, with Republicans vehemently objecting to the proceedings.

Both scenarios are troubling. If ruling on Section Three’s lack of self-execution is the only way the Supreme Court can craft a majority to keep Trump on the ballot, they should do so. Removing him from the ballot is worse for the country than these potential events. However, basing their ruling on whether the president is an “officer of the United States” avoids the looming threat of chaos after what should be a contentious election.

The United States Supreme Court will soon decide whether Colorado election officials may deny former President Donald Trump access to the state’s presidential primary ballot.

Initially, several Colorado Republicans and unaffiliated voters challenged the former president’s eligibility and requested an order prohibiting the Colorado Secretary of State from placing Mr. Trump’s name on the ballot. They alleged that Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment disqualifies Mr. Trump because he engaged in insurrection on January 6, 2021.

The trial court judge rejected the voters’ request, despite concluding that former President Trump engaged in insurrection on January 6, 2021. The judge ruled that she could not direct Trump’s removal from the ballot because Section Three did not apply to him. The judge held that the president was not an “officer of the United States,” and therefore was not included as a position which one could be barred from under Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment. U.S. Const. Amend. XIV, § 3.

In concluding that Trump incited insurrection, the trial court relied on evidence in the form of a report produced by the hyper-partisan House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack. This reliance is problematic. The January 6th Committee and its report were both openly hostile to former President Trump. Its proceedings were one-sided and lacked meaningful due process. Finders of fact – such as the judge in the trial court – should not be permitted to rely on this report in concluding that Trump engaged in an insurrection. Such reliance appears to violate the general prohibition on admission of hearsay evidence.

Nonetheless, the judge correctly concluded that the president was not an “officer of the United States.” U.S. Const. Amend. XIV, § 3. Both sides appealed the trial court’s decision to the Colorado Supreme Court.

In a 4-3 decision, the Colorado Supreme Court agreed with the trial judge’s conclusion that Trump engaged in insurrection. The Colorado Supreme Court, however, also ruled that the trial court had erred by concluding that the individuals and Colorado election officials were powerless to keep the former president off the ballot. To the Colorado Supreme Court, the president was covered by the phrase “officer of the United States.” U.S. Const. Amend. XIV, § 3.

The Colorado Republican Party and Mr. Trump asked the United States Supreme Court to review the case, urging the justices to settle the matter once and for all. In addition to Colorado, similar efforts to keep Trump off the ballot require resolution in at least 35 more states. The proliferation of these cases makes the U.S. Supreme Court’s involvement both timely and inevitable.

The Supreme Court will focus on whether Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment applies to a former president; whether Section Three is self-executing; and whether Trump’s speech on January 6, 2021, was protected by the First Amendment.

Landmark filed a friend of the court brief supporting former President Trump’s appeal. We did so after a careful analysis of the legal issues involved and a thorough review of the underlying due process violations leading to the “insurrection” determination.

Landmark’s full analysis is included in our Supreme Court brief. Our focus is whether Section Three is “self-executing,” whether former president Trump’s January 6 remarks were protected by the First Amendment, and what will be the practical and long-term political consequences if the Colorado ruling is allowed to stand.

Brandenburg Test:

What does the Supreme Court say about

calling for violence or lawbreaking?

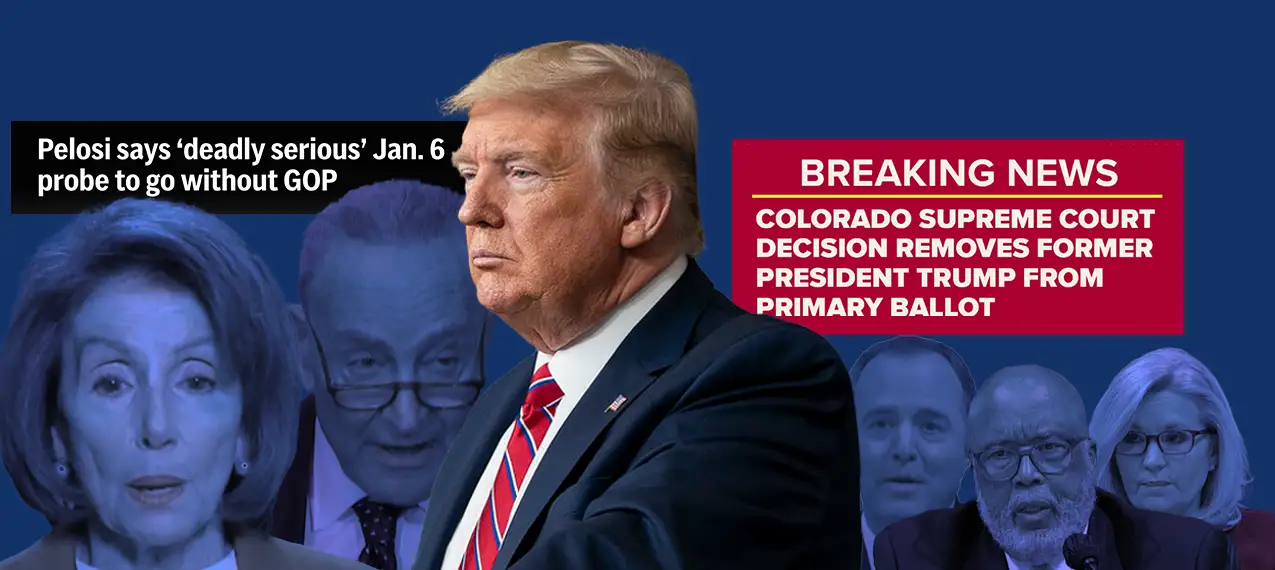

Bottom Line: The First Amendment does not protect speech if it is intended to incite imminent lawless action and is likely to incite such action under Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969).

Donald Trump argues that his speech at issue does not constitute incitement because his words were not intended to incite violence nor likely to do so. In his view, his words were benign. The Colorado trial court relied on testimony from Pete Simi, a sociology professor, to establish Trump’s intent. Simi stated that Trump has a history of extreme rhetoric and speaks in coded language to his followers. In Landmark’s view, Brandenburg’s intent requirement for incitement is a high bar that has not been met.

In Brandenburg v. Ohio, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed a Ku Klux Klan leader’s state conviction under the Ohio Criminal Syndicalism statute. Clarence Brandenburg invited a reporter and cameraman to a Klan rally where he was filmed saying, “We’re not a revengent organization, but if our President, our Congress, our Supreme Court, continues to suppress the white, Caucasian race, it’s possible that there might have to be some revengeance taken.” Id. at 446. He also used racial slurs and expressed his belief that certain groups “should be returned” to Africa and Israel. Id. at 447.

In a per curiam opinion, the Supreme Court held that “the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” Id.

What Does the Federal Criminal Code Law

Say About Insurrection, Incitement, and Riots?

Donald Trump’s critics argue that he engaged in and incited an insurrection. His defenders say 1) the events of January 6 constituted a riot, not an insurrection; and 2) he told supporters to be peaceful, not violent, so he did not intend either one to happen.

The federal criminal code addresses insurrections, riots, and inciting both. And the Supreme Court explains that since incitement is often speech, it requires a showing of intent to avoid First Amendment problems.

Bottom Line: Landmark argues that the failure to indict and convict Trump in a criminal court or impeach and remove him in Congress means his intent to incite an insurrection or riot has not been sufficiently established. It is premature for a state civil official or court to declare him disqualified from office and ineligible to be on the ballot.

Engaging in or Inciting an Insurrection

Whoever incites, sets on foot, assists, or engages in any rebellion or insurrection against the authority of the United States or the laws thereof, or gives aid or comfort thereto, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both; and shall be incapable of holding any office under the United States.

18 U.S.C. § 2383 (emphasis added). Notice that one of the law’s penalties is the disqualification from holding any “office under the United States.”

Inciting a Riot Another chapter of the criminal code addresses riots and the incitement of a riot. Someone who travels in interstate or foreign commerce or uses “any facility of interstate or foreign commerce” such as mail, radio, or television with the intent:

(1) to incite a riot; or

(2) to organize, promote, encourage, participate in, or carry on a riot; or

(3) to commit any act of violence in furtherance of a riot; or

(4) to aid or abet any person in inciting or participating in or carrying on a riot or committing any act of violence in furtherance of a riot; and who either during the course of any such travel or use or thereafter performs or attempts to perform any other overt act for any [specified] purpose…— [1]

Shall be fined under this title, or imprisoned not more than five years, or both.

18 U.S. Code § 2101. The next section of the code defines inciting or participating in a riot.

As used in this chapter, the term “to incite a riot”, or “to organize, promote, encourage, participate in, or carry on a riot”, includes, but is not limited to, urging or instigating other persons to riot, but shall not be deemed to mean the mere oral or written (1) advocacy of ideas or (2) expression of belief, not involving advocacy of any act or acts of violence or assertion of the rightness of, or the right to commit, any such act or acts.

18 U.S. Code § 2102.

The U.S. Supreme Court Explains Why Intent is Key to Incitement

It is important to distinguish permissible political speech from criminal incitement, as alluded to in Section 2102. Incitement is one of the very few exceptions to First Amendment protection. In a recent Supreme Court case, Counterman v. Colorado, 143 S. Ct. 2106 (2023), Justice Kagan discussed why the mental state of intent is necessary for incitement.

Like threats, incitement inheres in particular words used in particular contexts: Its harm can arise even when a clueless speaker fails to grasp his expression’s nature and consequence. But still, the First Amendment precludes punishment, whether civil or criminal, unless the speaker’s words were “intended” (not just likely) to produce imminent disorder. Hess v. Indiana, 414 U. S. 105…(1973) (per curiam); see Brandenburg, 395 U. S., at 447; NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware Co., 458 U. S. 886…(1982). That rule helps prevent a law from deterring “mere advocacy” of illegal acts—a kind of speech falling within the First Amendment’s core. Brandenburg, 395 U. S., at 449.

Counterman, 143 S. Ct. at 2115. More information: Independent Counsel Jack Smith’s Indictment: https://www.justice.gov/storage/US_v_Trump_23_cr_257.pdf

Is Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment Self-Executing?

Some argue a separate law is not necessary to have an individual declared ineligible under Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment. Anyone, including private parties, can force state election officials to have a candidate declared ineligible because the candidate engaged in insurrection. Section Three is just like other sections of the Fourteenth Amendment that have previously been found to be self-executing.

Landmark argues that Section Three is NOT self-executing, and that Congress must pass a law that would allow individuals, groups, and state officials to challenge the eligibility of individuals. The text, history, and case law all indicate that the Fourteenth Amendment’s drafters expected Congress to pass laws to enforce Section Three’s disqualification provisions.

Bottom Line: Congress has not passed a law empowering private parties to bring private causes of action in state courts to have Donald Trump declared ineligible. Therefore, the Colorado District Court and Colorado Supreme Court did not have the authority to determine whether Donald Trump engaged in insurrection and is therefore disqualified from appearing on the ballot.

The evidence supporting the argument that Section Three is NOT self-executing:

- Text of Fourteenth Amendment indicates that Section Three is not self-executing.

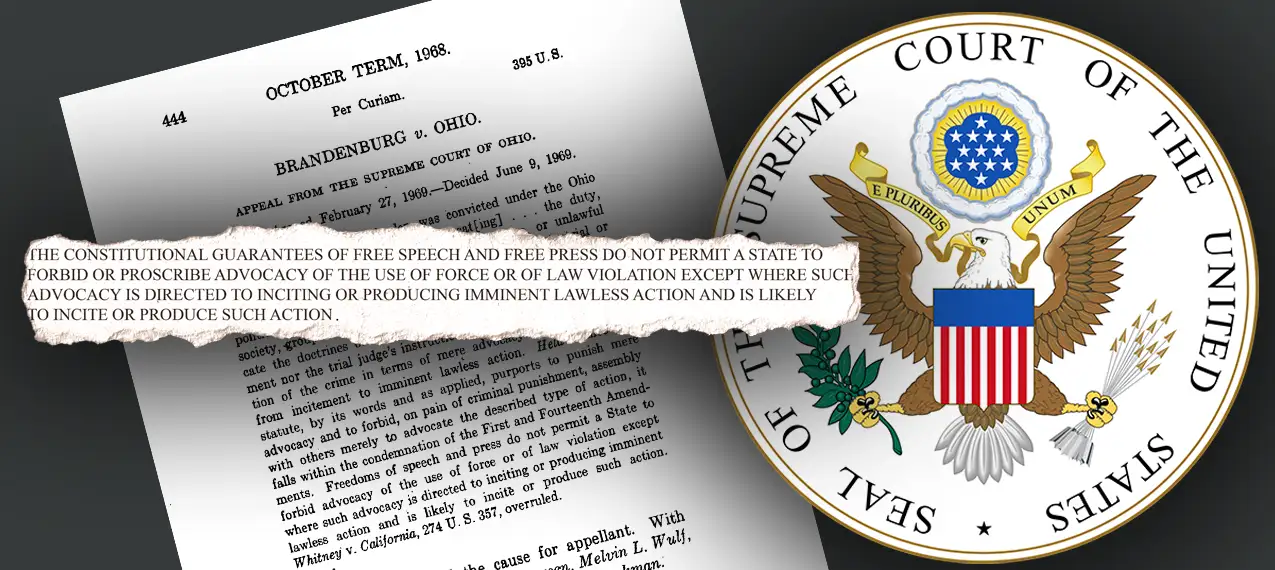

First, the last sentence of Section Three provides a mechanism for Congress to override the disqualification. It states, “But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.” U.S. Const. Amend. XIV, § 3.

Next, Section Five of the Fourteenth Amendment provides: “The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.” U.S. Const. Amend. XIV, § 5.

Congress – not the individual states – has authority to enact legislation to enforce the provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment. If it were evident that Section Three is self-executing, what purpose would Section Five serve?

- History, case law, and congressional action demonstrate that Section Three is not self-executing.

At the time of its drafting, Representative Thaddeus Stevens (a member of the Amendment’s drafting committee) noted that Congress would have to pass enabling legislation since the Joint Committee’s draft of Section Three “will not execute itself.” And the Congressional Record contains no mention of any members disagreeing with Representative Stevens’s remarks.

Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase’s ruling in In re Griffin, 11 F. Cas. 7 (C.C.D. Va. 1869) (Griffin’s Case), held that Section Three is not self-executing and that a party could only seek relief when a federal statute has authorized it. Griffin’s case was recognized as guiding precedent for decades. See, for example, Ex parte Ward, 173 U.S. 452, 454-455 (1899).

After the Fourteenth Amendment’s ratification, Congress repeatedly passed laws to enforce Section Three. The Enforcement Act, passed in 1870, established a cause of action to be brought by federal authorities to remove officials from office. The Enforcement Act also criminalized actions that would render someone ineligible under Section Three. The passage of the Enforcement Act clarifies the drafter’s intent that additional laws needed to be passed to enforce the provisions of Section Three.

What is the January 6th Committee?

Supporters of the January 6th Committee argue that its thorough investigation of the facts and hefty list of witnesses make credible the final report which it produced. Critics say the committee was biased from the start because all members were selected by Speaker Pelosi and failed to interview witnesses who may have contradicted its findings, leading to a partisan report.

Bottom Line: The House Select Committee tasked with investigating the January 6 riot has been widely criticized as a political project of Nancy Pelosi and the Democrats. The Committee was filled entirely by the former Speaker and included only two Republicans, both of whom had voted to impeach former President Donald Trump as an “insurrectionist” prior to the Select Committee’s establishment. The committee report is equally biased and should be regarded with skepticism rather than taken as proof of the facts asserted.

Why does Landmark call the January 6th Committee’s Membership Biased?

The House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack was a group of nine congressmen, seven Democrats and two Republicans, who were selected by then-Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi. Pelosi rejected two Republicans recommended to the panel by the Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, Representatives Jim Banks and Jim Jordan, for statements they had made which she felt would impact the committee work.

This move was widely criticized by Republicans, including by McCarthy in a weekly Minority Leader briefing, as an abuse of power and a clear move to politicize the committee. Pelosi’s decision to reject McCarthy’s selections in favor of her own was a “historic” decision to “deny the minority to even put their individuals on a committee,” according to McCarthy. In so doing, the Speaker blatantly violated House customs. The final members selected by Nancy Pelosi were Democrat Representatives Bennie Thompson, the chairman, Zoe Lofgren, Adam Schiff, Jamie Raskin, Pete Aguilar, Stephanie Murphy, Elaine Luria, and Republican Representatives Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger. The latter two were censured by the Republican Party for their participation on such a partisan committee and “mask[ing] Democrat abuse of prosecutorial power for partisan purposes.”

What was January 6th Committee’s Conclusion?

The committee interviewed more than 1,000 witnesses over the course of a year and a half. Many of the important witnesses included election officials who Trump had attacked, or former aides who had become critical of Trump since the end of his term, such as Cassidy Hutchinson. Meanwhile, Donald Trump, Kevin McCarthy, other congressional Republicans, and top Trump staffers defied subpoenas, meaning that the committee did not hear a great deal of testimony from key figures with opposing viewpoints. Upon the conclusion of the interviews, the committee held several public hearings with the same witnesses, before releasing their report which detailed the events of the January 6 riot. The committee concluded that the events of January 6 constituted an insurrection which Donald Trump incited, and that he should be prosecuted on several crimes, including obstruction of an official proceeding, conspiracy to defraud the United States, and aiding an insurrection against the United States.

The report has been criticized by prominent scholars, including Jonathan Turley and Alan Dershowitz, among others, for being one-sided and of little real value. The Department of Justice declined to accept the committee’s insurrection prosecution referral, despite the 800-page report. House Republicans released a counter report discussing security failures at the Capitol. Additionally, it was revealed in early 2024 that the committee had deleted one hundred files just before control of the House changed hands after the 2022 election. This has raised further questions about the partisan nature of the committee and its products. Despite these issues of evident bias, the committee report was admitted into the record as factual by the Colorado district court in December, during the hearing for Trump’s ballot access case.

Consequences of the Colorado Supreme Court’s Decision

The Colorado Supreme Court held that a state election official can decide whether a candidate is disqualified for office for being an insurrectionist, just like they do for candidates who are not U.S. citizens or are underage. If state election officials have this power, commonplace actions like occupying government buildings and political speeches to crowds who go on to destroy government property could disqualify an individual from serving in federal office.

Bottom Line: A state trial court does not have the constitutional authority to declare political candidates ineligible to run for president under Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment. Permitting private parties to bring these actions would mean Section Three could be used as a partisan political weapon to disenfranchise voters and undermine the electoral process.

Examples where political candidates could be declared ineligible to serve under Section Three:

- Kamala Harris supports Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests. In June 2020, then-Senator Kamala Harris expressed support for BLM protests/riots that resulted in damage to and barricades of federal courthouses.

- Representative Jamaal Bowman pulls a fire alarm. On September 30, 2023, Representative Bowman pulled a fire alarm in the United States Capitol as Congress worked to approve a stopgap spending bill to avoid a government shutdown. He committed a crime to interrupt the official proceedings of Congress.

- Senator Schumer warns justices on the steps of the U.S. Supreme Court. On March 4, 2020, Senator Chuck Schumer made the following statement in a pro-abortion speech outside the Court: “Republican legislatures are waging a war on women, all women. I want to tell you [Justice] Gorsuch, I want to tell you [Justice] Kavanaugh. You have released the whirlwind, and you will pay the price. You won’t know what hit you if you go forward with these awful decisions.” On June 8, 2022, U.S. Marshals detained an armed individual near the home of Justice Kavanaugh who stated that he was angry over the possibility that the Supreme Court would overrule Roe v. Wade.

- Representative Rashida Tlaib urges on pro-Palestinian protestors who disrupt Congress and injure police. Last Fall, pro-Palestinian protestors marched on the U.S. Capitol and engaged in a sit-in in the Rotunda, demanding a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas war. This event turned violent with several demonstrators arrested for assaulting police officers. Representative Tlaib spoke to the crowd before the event, stating, “I think the White House and everyone thinks we’re just gonna sit back and let this just continue to happen. No!”

The Second Impeachment of Donald Trump

The Colorado Supreme Court ruled Donald Trump is ineligible to hold office because he engaged in insurrection. However, he has not been criminally charged with inciting or engaging in insurrection. The only time the issues of incitement and insurrection have been raised in a proceeding conducted with appropriate due process was his 2021 impeachment trial.

Bottom line: The House of Representatives impeached Donald Trump on one count of Incitement of Insurrection for the events of January 6, 2021. The Senate acquitted

What is Impeachment?

Impeachment is a process for bringing charges against a government official for misconduct. The Constitution lists “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors” as impeachable offenses. U.S. Const. Art. II, § 4. Impeachment begins in the House of Representatives, where Articles of Impeachment are drafted. If an article passes with a simple majority, the official is impeached. The Senate acts as a High Court of Impeachment to hear the case. If the Senate votes to convict by a two-thirds majority, the official is removed from office and barred from holding office in the future. U.S. Const. Art. I, § 3. Presidents Johnson, Clinton, and Trump have been impeached by the House and acquitted by the Senate.

What was the conclusion of Trump’s impeachment trial?

Oral arguments began in the Senate on February 10, 2021. In an expedited trial, the House impeachment managers argued that Mr. Trump’s rhetoric following the election created a risk of violence that was predictable. Trump’s lawyers noted his speech was protected political speech and argued that the managers could not prove it encouraged violence. Donald Trump was acquitted on the charge of Incitement of Insurrection on February 13, 2021.

Neither chamber of Congress has an established standard of proof for impeachment proceedings. Rather, according to a Congressional Research Service report on the issue, “both the House and Senate have sought to ensure that individual Members remain free to make their own determinations.” Members are “guided by their individual conscience and judgment, and their oath to do ‘impartial justice.’” The standard of proof is relevant to the case before the U.S. Supreme Court. The Colorado trial court used a high civil standard of “clear and convincing” proof, but that is still lower than the criminal “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard. This highlights the problem of having a state civil court determining whether Donald Trump incited insurrection. If he had been indicted for inciting an insurrection in a federal criminal trial, it would have required higher proof of his intent.

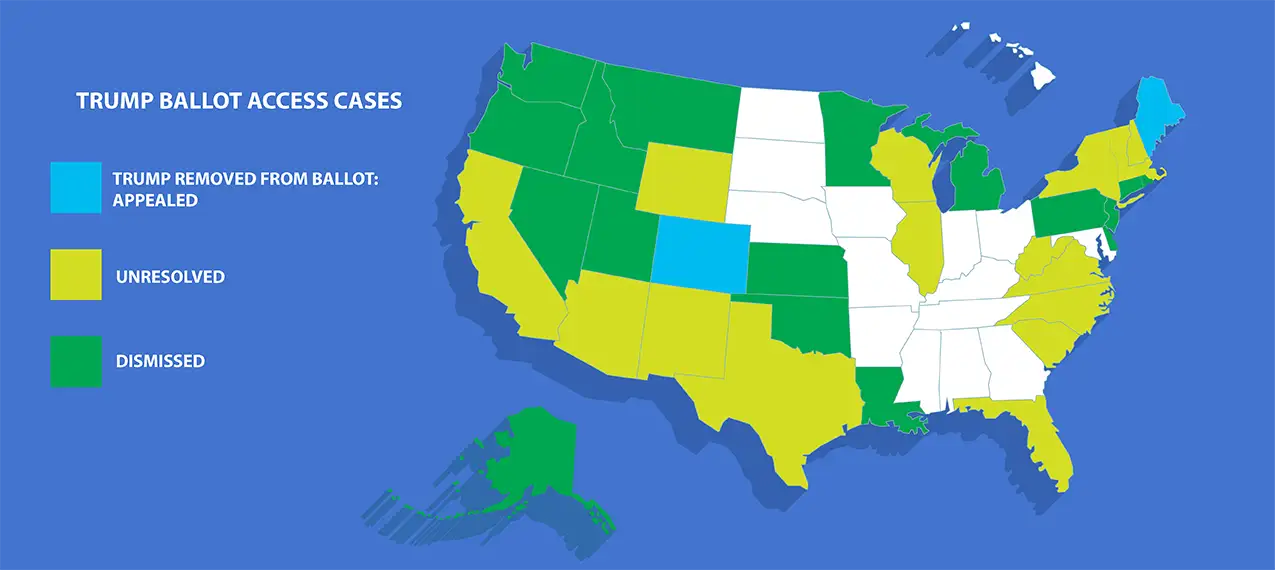

Summary of Efforts to Remove Donald Trump from State Ballots

Bottom Line: The nation needs a uniform decision as to whether Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment applies to Donald Trump to prevent chaos. If no such ruling is provided, states will continue to litigate and rule on the issue in different manners, creating an electoral nightmare in which Americans in one state may be prevented from voting for their preferred candidate, while their neighbors in others are not.

Summary of Current Removal Efforts:

As of February 2, lawsuits have been filed in 35 of 50 states to remove Donald Trump from the ballot. In two of these, Colorado and Maine, Trump has already been removed from the ballot. In Colorado, this was mandated by the State Supreme Court; in Maine, it was unilaterally carried out by the Secretary of State.

In fifteen of these states, at least one lawsuit is currently pending in district or appeals courts. In Vermont, Texas, New Hampshire, New York, New Mexico, and California there are lawsuits currently pending in Federal District Court to remove Trump from the ballot. In West Virginia, Florida, and Arizona lawsuits seeking the same end were dismissed, but then appealed to the corresponding Federal Appeals Courts, the Fourth, Eleventh, and Ninth, respectively. In Wisconsin, North Carolina, and Wyoming, there are pending lawsuits at various levels in state courts; the case in Wyoming is pending appeal to the Wyoming Supreme Court. Additionally, in Illinois there is a pending appeal to a challenge with the State Board of Elections and in Virginia there is an administrative challenge before the Richmond City Circuit Court. In Massachusetts a private citizen filed a complaint with the State Ballot Law Commission, which was dismissed and then appealed to the State Supreme Court. In some of these states, some lawsuits were filed and then dismissed. However, all have at least one active lawsuit or legal complaint currently pending.

In the remaining eighteen states, lawsuits have been dismissed or adjudicated in Trump’s favor. Lawsuits in Alaska, South Carolina, Connecticut, Delaware, Idaho, Kansas, Louisiana, Minnesota, Montana, New Jersey, Nevada, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Utah, and Washington met the former fate. In Michigan a state appeals court determined that Trump could not be disqualified under Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment. In Oregon, the State Supreme Court held similarly, though they noted if the Supreme Court upheld the Colorado decision, petitioners could file a new lawsuit in state court.

SUPPORT LANDMARK LEGAL FOUNDATION

We are truly facing existential threats to our individual rights and liberties, the Constitution, and our national character. If unchallenged, this assault on our very way of life will ruin our great nation. With your financial and moral support, Landmark is not going to let that happen without a fight. Will you join us?

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Never miss an update from Landmark Legal Foundation as we continue the fight to preserve America’s principles and defend the Constitution from the radical left.

Landmark will NEVER share your contact information and we will not flood your inbox.